By Sheli Smith, PhD - PAST Foundation

October 29, 2010

US Minerals Management, now known as Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement (BOEMRE) began a program in 1996 known as Rigs to Reefs. The program encourages scientists from various disciplines to work together in understanding how shipwrecks become reefs and reefs contribute to the formation of shipwreck sites. In the following two articles Dr. Cheryl Morrison, a geneticist, of USGS – Biological Resources Division and Dr. Sheli Smith, a maritime archaeologist, of PAST Foundation examine the GulfOil from the perspective of biology and archaeology. Almost as soon as a shipwreck reaches the bottom it begins to seek equilibrium with its environment simultaneously disintegrating and providing a habitat for deepwater species. The GulfOil, with its relief and degrading steel, supply macro and micro fauna the necessary variables to survive. The robust reef provides ecologists, biologists, geneticists, and geologists with abundant information regarding populations, diversity and health of the reef. The ship remains supply archaeologists with information about the wrecking event, the life aboard the vessel, the cargo, the technologies of the time, and the site formation. Archaeological research thus looks both back in time for historical information and forward toward modeling site formation. Together the multi-discipline approach examines the past, the present and the future.

Yesterday we prepared all day for the long dive that would allow the archaeologists, the ecologists, geneticists, and geologists to study and collect samples. Dive plans are complicated and take about the same coordination as choreographing a ballet. Every move must be thought out and all the kit secured to Jason before the dive. There is no returning to the surface for a spare part or another specimen tube. So, well before the dive a plan is drawn up and everyone knows where the specimens will be placed and when the tasks will be performed. In fact, there is a map of the front and side porches aboard Jason. As they are filled with specimens, the data logger records what is in each box or collection tube.

A shipwreck is a bit different but still works in concert with the biology and geology. The priorities in terms of documentation are laid out with leeway to adopt and change. The maps and photographs, if they exist, are pored over so that everyone has an image already in their head. In the case of the GulfOil there exists a ca. 1912 photograph of the ship, probably taken not long after it was launched. The image comes from a glass plate negative and thus is incredibly clear and detailed. By blowing up the image we were able to focus in on key components of the ship that would be landmarks for us as we surveyed.

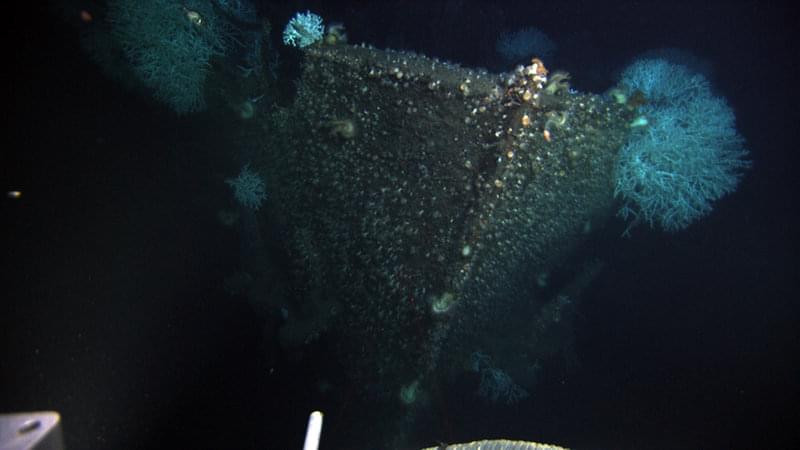

Rising over 10 meters off the seafloor, the bow and stowed anchors bear mute testimony to the 1942 catastrophe. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEMRE. Download larger version (jpg, 3.2 MB).

Prepped with our plan, photograph and sidescan images, we dropped down on the site. Our plan took us first to a debris field east of the hull. The debris field was discovered through sidescan sonar and revealed a low-lying scatter on the otherwise flat seafloor. Within minutes of reaching the bottom, we sighted a ventilator and some deck grating. Dan Warren, the lead archaeologist, hypothesized that this was the location of the first torpedo strike. Reports from survivors told of being struck first in the bow and then in the stern.

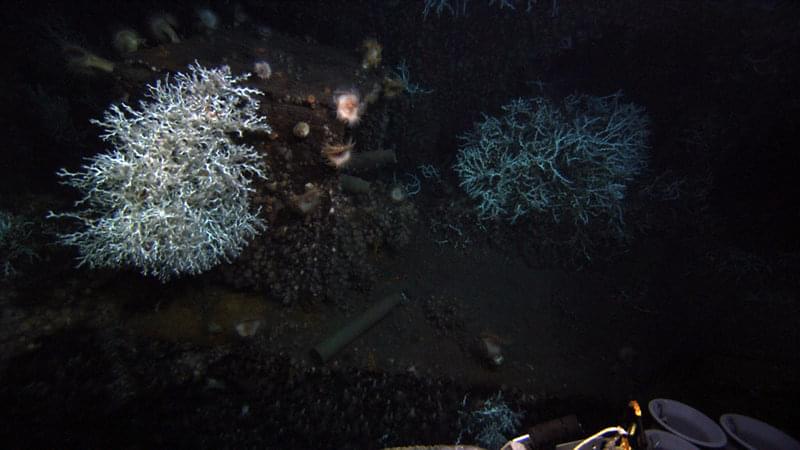

Empty gun casings are scattered across the rear deck near the 4-inch gun mounted at the stern. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEMRE. Download larger version (jpg, 2.9 MB).

The first order of business was a reconnaissance around the hull to look for entanglements and get our bearings on the wreck. We found the ship came to rest stern first leaning to port, thus placing most of the entanglement hazards on the portside. We found both masts collapsed but still lying on the deck. The top of the wheelhouse is gone, as is the stack, but the hull is intact.

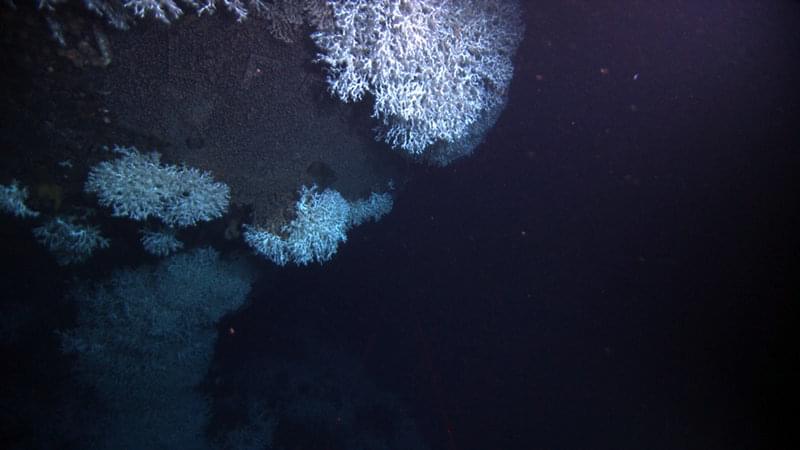

In touring the wreck we found huge colonies of Lophelia, which I contend should be renamed Lophelia obscura. The coral covers all of the wheelhouse and stern cabins as well as the catwalk stretching the length of the amidship area. The decks are free of Lophelia, but everything sticking up into the water column is covered. The hull below the waterline except at the very stern is also free of Lophelia. The lack of Lophelia may be due to many reasons but the two possibilities that pop up are – the antifouling paint below the water line is still visible and deters the growth of Lophelia and/or Lophelia requires an open environment exposed to good current on which to grow.

As we continued our tour around the hull we spotted all the features that are prominent landmarks including the four-inch gun on the stern and the overturned box of empty, brass shell casings. Clearly discernable across the transom were the letters G U L F O I. Lophelia draped over the transom obscured the last two letters of the ship’s name.

Although partially hidden by draping Lophelia, the letters G U L F O I are still visible across the transom. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEMRE. Download larger version (jpg, 2.7 MB).

Large rusticles drip from the scarred hull of the GulfOil where the torpedo ripped through. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEMRE. Download larger version (jpg, 3.9 MB).

Once the reconnaissance was complete, we began the slow but satisfying task of capturing a photo mosaic of the entire starboard side of the hull. The runs were made at a constant distance from the hull of 3 meters with frame captures every 15 seconds. Each lane moved aft 4 meters. Thirty five lanes later we had discovered the two visible torpedo holes, one in the bow and one in the stern with a third concave impression just aft of the wheelhouse. Since the ship’s transom sits only 2 meters above the seafloor while the bow rises 10 meters above, the amidship damage may be the result of hull failure after the second torpedo or may indicate a third torpedo strike that is now covered by sediment. Historic accounts from the surviving sailors report that the catwalk collapsed when the second torpedo hit the stern, however the collapsed catwalk is directly above the concave hull near amidships. It is possible that two torpedoes hit almost simultaneously flooding both the engine room and the amidship resulting in the extremely rapid sinking of the GulfOil. Indeed, one of the moments that caught everyone’s attention was when the lights of Jason illuminated the intact boiler sitting just inside the hull near the entry hole of the sternmost torpedo.

After the photo mosaic of the side we ran two photo mosaic transects down either side of the hull centerline. From the mosaics and reconnaissance we gathered specific locations to return to for high definition camera shots. The data from the mosaics and still shots will consume many a research hour in the future as we piece together our knowledge of the GulfOil and her final moments.

At the end of this task, the team switched to a careful documentation and collection of geologic and biological samples so that we can further understand the relationship of shipwrecks to reefs at differing depths. The importance of a combined study cannot be overstated. Shipwrecks provide a location for reef development and at the same time the reef on a vessel contributes to the type of preservation and site formation of cultural resources.