By Chuck Fisher, PhD - Pennsylvania State University

November 3, 2010

Our final dive of this expedition was an exploratory dive to an area 7 miles to the SW of the site of the Deepwater Horizon disaster and to the same depth as that site. This dive site had been previously identified by BOEMRE scientist Bill Shedd, Dr. Harry Roberts from LSU and myself using the same kind of approach described in the log from the 2007 Expedition to the Deep Slope. Our purpose on this dive was to discover, characterize and sample new hard bottom communities in the vicinity of the Macondo well and establish long term observatory stations in these communities. We have actually picked a total of 25 sites we want to investigate eventually, but this was the first of those to be visited by ROV. It was selected because both model and empirical data suggested that the deep water currents during the period that oil was leaking from the well traveled in this direction and at this depth. At 3:30 pm local time on November 2, we encountered a colony of the hard coral Madrepora sp at 1400m depth. Although parts of the colony appeared normal, upon close examination other branches were clearly covered in a brown material, apparently sloughing tissue, and producing abundant mucous. Pieces of this coral and the immediate area were sampled, and we continued our dive.

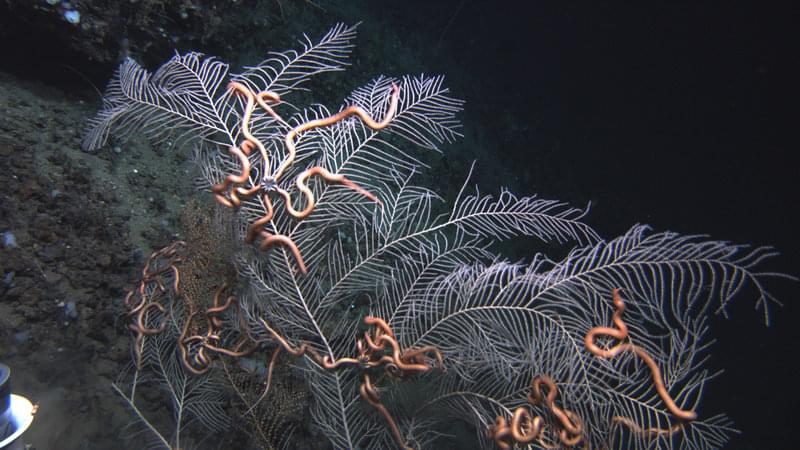

The gorgonian sea fan Callogorgia americana and symbiotic brittle stars from a site at approximately 350 meters depth in the Green Canyon area of the Gulf of Mexico. In the bottom left of the image are some small, brown anemones that have colonized a portion of the skeleton of the sea fan. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEMRE. Download larger version (jpg, 2.1 MB).

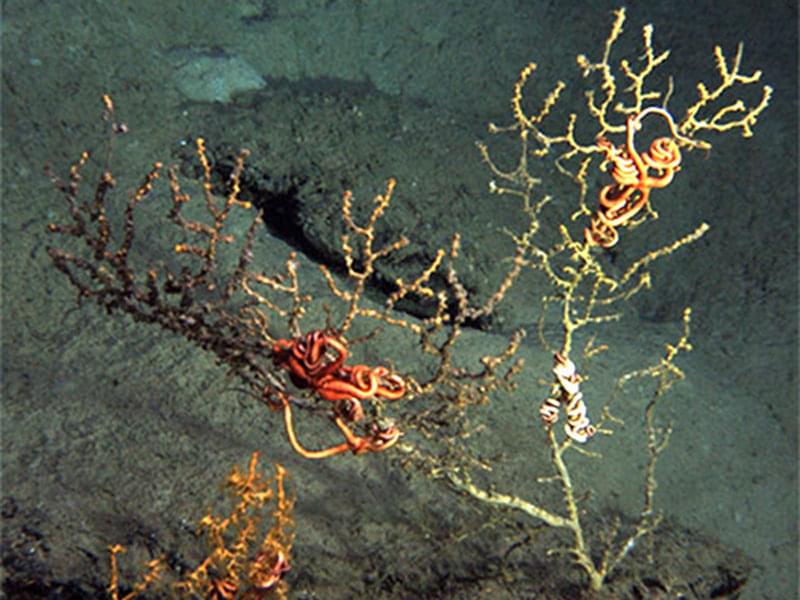

About 400 meters away from this location we encountered a community of gorgonians (soft corals) on two large carbonate slabs and associated boulders. Within minutes of arrival at this site, it was clearly evident to the biologists on board that this site was unlike any others that we have seen over the course of hundreds of hours of ROV and submersible time studying the deep corals in the Gulf of Mexico over the last decade. Extensive portions of most of the coral colonies appeared to be either recently dead or dying. Most of the sea fans (gorgonians) had large areas that were bare of tissue, covered with brown material, and/or had tissue falling off the skeleton. Many of the colonies appeared recently dead, with no living coral tissue, still covered with decaying material, and also a notable lack of colonization by other marine life as would be expected on coral skeletons that had been dead for long periods of time. Additionally, many of the brittle stars that are the typical symbiotic partners of these types of corals appeared to be dead or extremely moribund. Many of the dead and dying coral colonies had these discolored and immobile brittle stars still attached.

A single colony of coral with dying and dead sections (on left), apparently living tissue (top right) and bare skeleton with very sickly looking brittle star on the base. Image courtesy of Lophelia II 2010 Expedition, NOAA-OER/BOEMRE. Download image (jpg, 148 KB).

The team realized that it was important that we carefully document this site and that what we were observing was ephemeral: unlike every other site we have visited so far, this site was in the throes of a dramatic event and is likely to look very different when we return in the future. So, we proceeded to carefully mosaic the entire central portion of the site, including all of the corals except a few isolated colonies on boulders tens of meters away from the central area. We also made a higher resolution photomosaic of a portion of the site with the highest coral diversity and density. Since most of the corals were fan corals, we complemented this documentation with careful image collection from the side of many of the corals.

In addition to the detailed and methodical imaging of the site and fauna, we collected a variety of samples that may help us to understand what happened here. We took small pieces of coral from each apparently different species for genetic identification. We fixed some of the samples on the sea floor in a fixative that will allow investigation of the proteins the corals were expressing on the sea floor and investigations of genetic damage they may have incurred. We also sampled both dead and live corals, brittle stars, anemones, and even mud for laboratory analyses and fingerprinting of hydrocarbons. These analyses will include tests to determine if there is still evidence of whatever chemicals may have impacted these animals in their tissues or the sediment beneath them.

We hope that the data from the samples we collected at this site will provide some chemical evidence for exactly what caused the extensive damage to this deep water coral community and lead to a better understanding of what happened here. However, it may have been caused by a plume of toxic water that passed through this area many months ago and the chemical evidence may have washed away with drifting sediments and dying tissue. Nonetheless, the team will use all the tools at our disposal to better understand what happened here and communicate that information to all of you. Because we also deployed some markers at the site, we will be able to return here in the future and confidently re-image the same colonies, even if their appearance has changed dramatically. In fact, we are planning on a return visit during our cruise with the submarine Alvin in December this year.