By Christopher German, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

March 7, 2010

Today we’ve been traveling north and taking time out for reflection and recuperation. Indeed, I spent the first half of the day asleep, a late contender for this voyage’s Golden Blanket Award. We finished our last conductivity, temperature, depth (CTD) drop around midnight, Friday, and since I hadn’t managed more than three hours sleep at any one time over the past few days, I decided not to set my alarm and to skip breakfast. Even so, imagine my surprise when I woke up at 12:15 p.m. only to find I had also missed lunch!

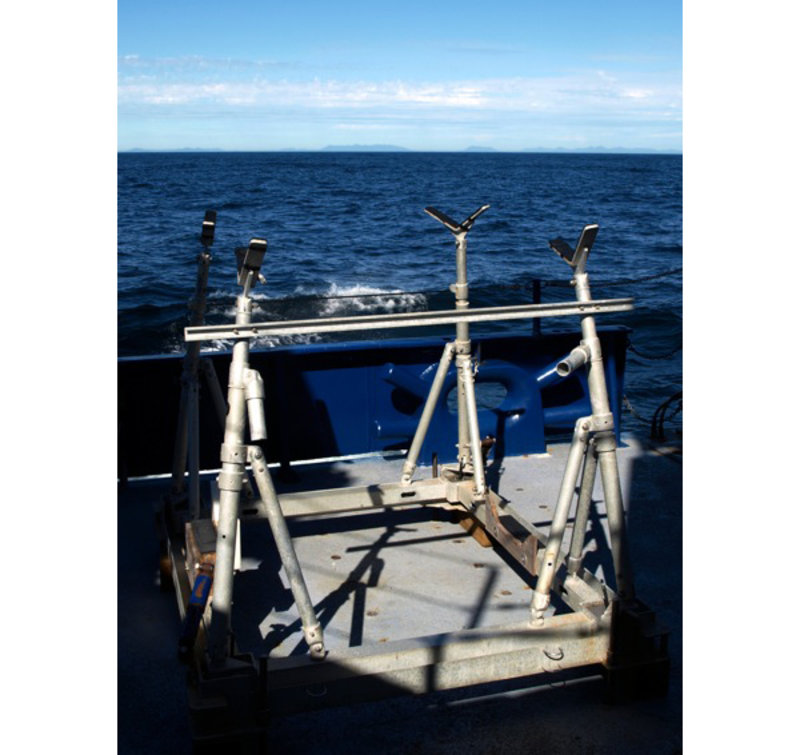

Gone, Baby, Gone. For much of the past five years, this kind of view has been one of my favorites. It indicated that the autonomous benthic explorer, ABE, was at the bottom of the ocean and chances were (if I was on the ship) it was tracking down new vents in previously unexplored parts of the deep ocean. Image courtesy of INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2010. Download image (jpg, 98 KB).

Heading into the lab I found a throng of happy (but exhausted) biologists. After we finished our last CTD station, Andrew Thurber and his gang completed two further benthic (sea bottom) trawls, which recovered (among other things) animal remains indicative of a cold seep. Fantastic! Another new target for future investigation.

Of course, we all still feel a little deflated by the loss of our long-serving and trusted autonomous underwater vehicle, ABE (autonomous benthic explorer). Together with Dana Yoerger as ABE expedition leader, I have participated in five cruises with ABE (once a year from 2004 to 2008), extending from the Southwest Pacific to the Indian Ocean, aboard U.S., British, German, and Chinese research ships and locating more than 12 different vent sites. Nobody ever feels good about losing any kind of scientific equipment.

But in ABE’s case, there is an up-side. Based on more than a decade of pioneering use, the Sentry — a new and improved explorer model — has been brought on line. Dana Yoerger and Al Duester will be heading back out to sea with Sentry later this month in a new exploration of the Galapagos spreading center. Still, ABE will always have a special place in my heart as the machine that we used to find the first vents in a number of different places. In particular, I am referring to the pursuit of our Census of Marine Life project, ChEss, tracking down the first vents in the South Atlantic and Southwest Indian oceans.

The coolest place on Earth? With southern Chile in the background (photographed just before the sun rose over the mountains), this picture contains (hidden beneath the waves): three separate tectonic plates, two or more active sites of seafloor fluid flow, and one last reported location of ABE. It took me seven years of dreaming, cajoling, begging, and planning to get down here to carry out our first exploration. I wonder how long it will be until I come back? Image courtesy of INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2010. Download image (jpg, 64 KB).

So perhaps it is fitting that the last thing ABE did, scientifically, coincided with the last exploration I shall be conducting for the decade-long Census of Marine Life: tracking down vent-sites in the area I had waited longest to explore. (Lisa Levin and I first started planning to come here in January of 2003.) It is a setting that I consider to be one of the coolest places on Earth: the place where the mid-ocean ridge and subduction (a geological process where one crustal plate edge is forced under another) zone under the Andes meet. Given a subduction rate of about 10 centimeters (cm)/year, we estimate that ABE will be swallowed up beneath the continental margin about 16,000 years from now.

But fear not! That is not the end of the story! As a subducting plate sinks, a significant part of the upper crustal material, along with components of the overlying sediments and anything buried within those sediments — can you see where I’m going with this? — will melt and rise upward beneath the Andes to erupt as volcanic lava. So in the spirit of our engineers, as well as in the world’s most impressive geological recycling center, we can be quite clear: ABE will rise again!