By Benjamin Maurer, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

February 28, 2010

A magnitude 8.8 earthquake shook Santiago early Saturday morning. We were miles off shore in water 2,600 meters (8,530 feet) deep, running operations on the seafloor with the multicorer. The water there is deep enough that the tsunami passed us as a slow and gentle rise in sea surface height of less than 30 centimeters (about 11 inches). With 2 m (6.5 ft) tall swell rocking the boat, no one noticed the tsunami passing by the research vessel (R/V) Melville.

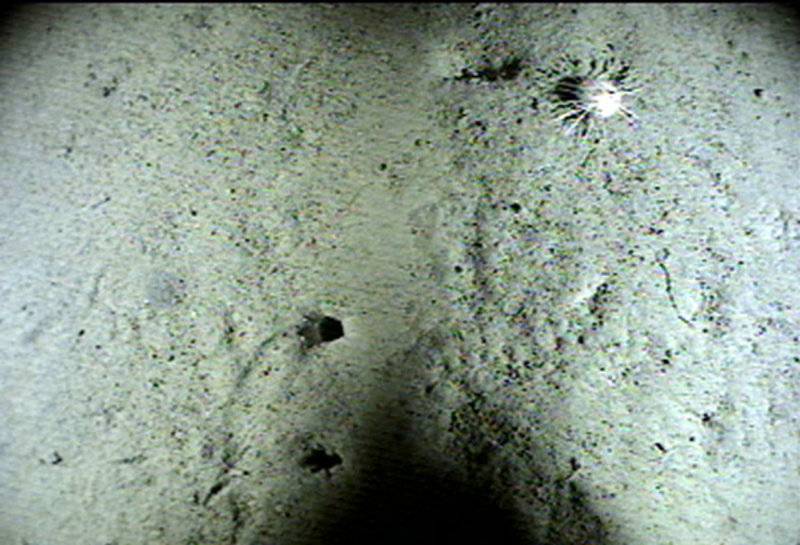

Video taken from the seafloor at 2600m depth, as the multicore lands and takes a sediment sample amount deep sea fauna. Video courtesy of INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2010. Download (mp4, 8.1 MB).

Though we weren’t in danger on the ship, many members of the science party are Chilean and have friends and families ashore. It’s difficult to get in touch with people in Santiago right now, but nearly everyone has gotten through to their loved ones via satellite phone, and it seems that they’re doing all right. Our hearts go out those who weren’t as fortunate.

Ben Maurer splices the electronics into the winch cable. Image courtesy of INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2010. Download image (jpg, 74 KB).

Aboard the Melville, science continues. For the last two days, I’ve been working on installing and testing a prototype real-time video system for the multicorer, a large heavy instrument used to take sediment samples from the seafloor. We mounted a camera and two lights to the frame of the multicorer, and I’ve been splicing the electronics into a 10,000 m (32,808 ft) cable and waterproofing the connection with glue and two types of tape. It took me two attempts over the better part of two days to get the connection working, but yesterday I finally got a clear image of the ship's deck from the camera on the monitors in the main lab. Hooray!

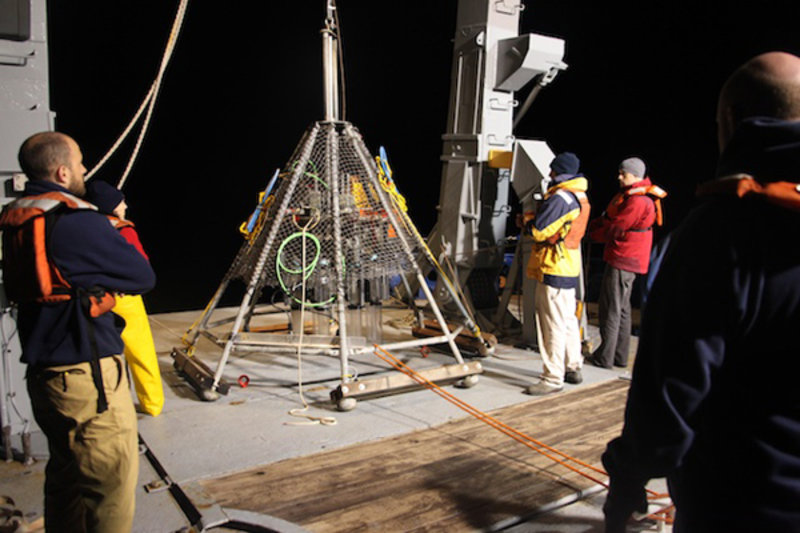

The multicorer before its first dive. Image courtesy of INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2010. Download image (jpg, 94 KB).

An image of the seafloor 2,600 m (8,530 ft) below the ship. Image courtesy of INSPIRE: Chile Margin 2010. Download image (jpg, 132 KB).

Around midnight, the conductivity, temperature, depth (CTD) instrument came back aboard. There was a rush of activity as everyone huddled around the rosette, scrambling for water samples. Meanwhile, as Danny Richter sampled the water for trace elements, we prepped the multicorer to go over the side. It’s a heavy, awkward instrument, but with three people manning taglines we got it in the water without too much trouble. It took more than an hour to lower it down to the seafloor.

When we were close, we flicked on the lights. Everyone leaned closer to the monitors, hoping to get a glimpse of the bottom through the silt. It felt like the whole science party was awake and focused on those screens. After 10 eternal minutes, the bottom slowly came into focus from behind the marine snow! Brittle stars, animal burrows, worms wiggling along, little creatures scuttling along the sediment. It was amazing to get a good look at what was going on more than two miles beneath the boat, and to get a close look at the site where we’d be sampling.

At 8:30 Sunday morning, after 23 straight hours of hard work on the video system, I crawled up into my bunk and fell asleep, content and thankful.