Published October 9, 2019

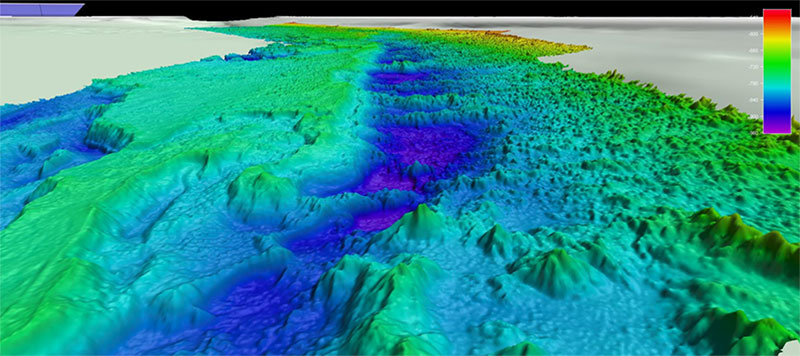

High-resolution multibeam bathymetry of the Stetson Mesa north region collected by the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research and NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer. The complex seafloor topography and thousands of mound features create important habitat supporting a diversity of marine life. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research.

About a hundred miles off the coast of Georgia and Florida lies a strange ecosystem at the bottom of the sea. It’s an underwater landscape of coral mounds that stretch as far as the eye (or at least the camera on a remotely operated vehicle) can see.

For thousands of years, corals have been growing and dying in this region that lies 600 to 800 meters (1,970 to 2,625 feet) below the ocean’s surface. Accessible only by submersible or autonomous vehicles, the “Million Mounds” region has drawn NOAA physical scientist Derek Sowers and other scientists to understand why and how the corals got there.

“It’s an astounding complex of mound features, just thousands and thousands of them,” said Sowers, who is leading a mapping expedition aboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer to the area this month. It’s the third time Sowers has been on an exploration mission to the Million Mounds ecosystem.

Using multibeam sonar, NOAA scientists and partners will be looking for the geographic limits of the coral zone in order to better protect it from things such as crab pots and bottom-trawling nets which could damage the coral. Members of the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council designated 60,000 square kilometers between North Carolina and the Florida Keys as deep-sea coral Habitat Area of Particular Concern in 2010, primarily to reduce trawling impacts, and they continue to study the area. Several areas within the protected zone remain open to fishing for golden crab, royal red shrimp, and wreckfish.

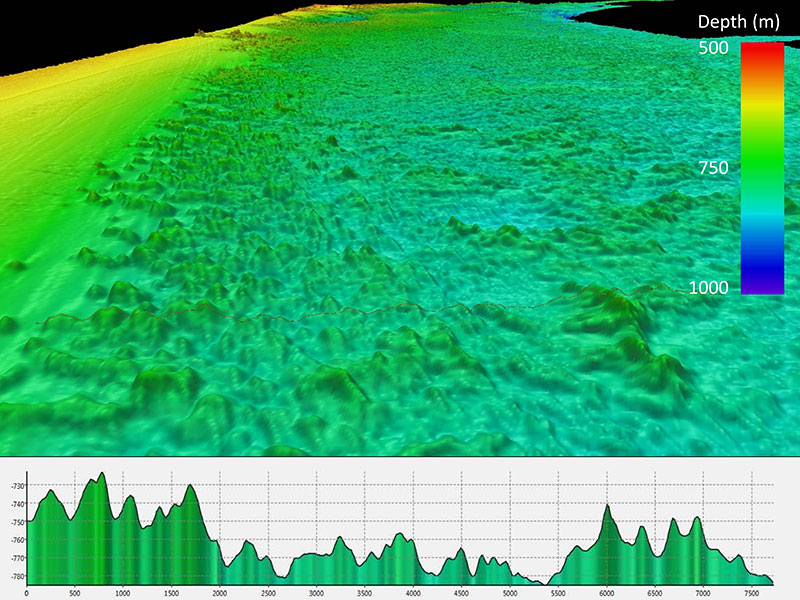

Multibeam bathymetry data collected by NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer showing the three-dimensional topography and profile of Million Mounds. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research.

Sowers says the ancient coral ecosystem acts much like an old-growth forest, providing habitat, shelter, and food for a variety of marine life.

“You have thousands of years of growth of coral skeletons, which then die and the calcium carbonate stays behind. Living coral then grows on top of the skeletons,” Sowers explained. “The structure provides a lot of nooks and crannies for life to hide in. It’s a complex habit for a lot of marine species.”

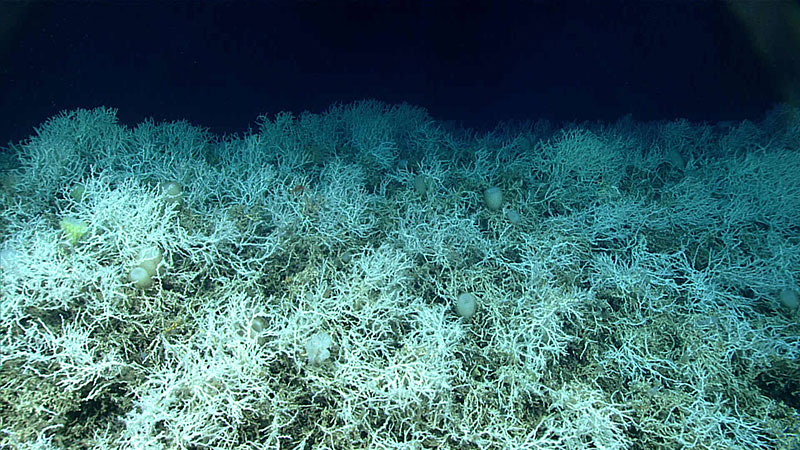

The Million Mounds ecosystem is primarily made up of Lophelia pertusa, a coral that prefers water below 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Farenheit) and grows several meters in diameter and 1 to 3 meters (3 to 10 feet) high. Some living Lophelia coral off the coast of Florida is estimated to be 700 years old, although it is fragile and easily broken by strong bottom currents or getting bumped by fish or other large creatures. Lophelia reefs are carpeted with a dense layer of living and dead coral rubble. The South Atlantic region is home to thriving Lophelia ecosystems that may be among the most extensive in the world.

Unlike tropical corals, deepwater corals thrive in darkness. As a result, deepwater coral polyps do not contain the symbiotic algae that provide their tropical cousins with color and some of their nutrition. The corals that Sowers has been exploring are slow-growing and white. They sift food from the fast-moving Gulf Stream, which flows from three to five miles per hour through the Million Mounds ecosystem.

The current supplies food and removes sediments that would otherwise smother the coral polyps. The corals are also typically found along rocky ledges or in narrow regions.

Dense fields of Lophelia pertusa found on the Blake Plateau knolls, just outside Stetson-Miami Terrace Deepwater Coral Habitat Area of Particular Concern. The white coloring is healthy – deep-sea corals don’t rely on symbiotic algae, so they can’t bleach. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Windows to the Deep 2019.

Scientists first discovered the deep-sea coral ecosystem in the 1960s with the Johnson Sea-Link submersible operated by the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution. More recently, a 2014 Okeanos expedition mapped a large portion of the coral ecosystem in a place called the Blake Plateau, Sowers explained.

The 2014 expedition mapped a portion of the Stetson Mesa region while surveying for eight days with the ship’s multibeam sonar, an effort that Sowers likened to a “sneak peek” of the coral gardens below.

“It was pretty stunning,” he said. “As you move north, the seafloor changes and you get more complex and rugged terrain – much of which is still topped with coral mound features.” Since the 2014 cruise, OER has conducted four additional missions exploring in this region, with the current cruise being the sixth.

In 2018, during the DEEP SEARCH expedition, a partnership between NOAA, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, and U.S. Geological Survey, scientists observed of a massive Lophelia reef further east, about 165 miles off the coast of South Carolina. This area was partially mapped by OER, and the DEEP SEARCH team of scientists confirmed the area was heavily populated with Lophelia reefs while diving in the Alvin submersible.

This month, Sowers and others are returning to determine the eastern boundary of the Million Mounds ecosystem and whether it is connected to the Lophelia reef seen in 2018.

“We have talked to scientists and managers in the region to learn about their top ocean exploration priorities and why these priorities are important,” Sowers said. “They said this region is intriguing, but we need more information on the coral extent and the density.” This month’s cruise will further map coral reefs inside and outside of the protected habitat area to see if there are differences in coral habitat density that may inform future management decisions.

Sowers has been lucky enough to return to this deep coral undersea realm on several cruises, each time learning new things about a largely unexplored world.

“For those of us that get to explore it remotely making terrain maps from sonar data, you gain an appreciation of what an amazing place it is,” Sowers said. “You are always wondering what’s down there and what the habitat actually looks like up close. To come back on a cruise to do more detailed exploration with OER’s remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and see these areas in high-definition video is stunning. Then we get to stream this imagery off the ship in real time to anyone with an internet connection so they can explore with us – it’s a lot of fun.”

The Okeanos Explorer left Rhode Island on October 5 and is scheduled to arrive in the coral habitat by October 9.

Learn more about Okeanos Explorer expeditions to the region: