Published September 27, 2019

Fishermen have used sonar to find their prey for decades, but oceanographers have only recently discovered the benefits of scanning the water column for tiny bubbles that may reveal secrets on the seafloor. In May 2009, as NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer was conducting its first shakedown cruise off the California coastline, NOAA scientists found something surprising. As they were testing a brand new multibeam sonar device attached to the hull of the ship, they began seeing readings that indicated a plume of something rising from the seafloor.

Mashkoor Malik, a physical scientist with the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research who was leading the science team on the shakedown mission, remembers the shock of the discovery.

“As we were transiting, we discovered a huge plume along the Mendocino Ridge,” Malik said. “It rose about 1,400 meters (4,590 feet) high from the seafloor.”

Physical scientist Mashkoor Malik (right) and intern David Armstrong (left) edit multibeam data using the software CARIS during the shakedown mission. Image courtesy of NOAA.

The Mendocino Ridge is a narrow sub-sea mountain range that is part of the Mendocino Fracture Zone, which extends more than 5,000 kilometers (3,100 miles) across the eastern Pacific Ocean. The Mendocino Ridge, where the Okeanos Explorer was sailing, extends west from Northern California and in some places rises to more than one kilometer above the ocean basin floor. This was the first time that multibeam sonar, which had been used for undersea mapping, was used to detect seeps of methane gas bubbling up from cracks in the seafloor. One of the goals of the cruise was to find a methodology to optimize settings on the multibeam sonar to detect gas leaks.

It worked.

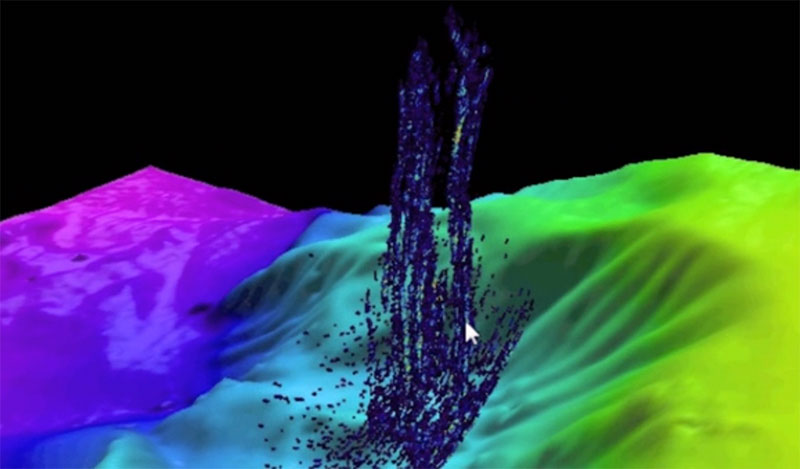

The team collected data from the sonar to assemble a 3D video of the plume, which looks like a sparkly blue fountain erupting from the sea bottom. Malik said that both the technology used and the discovery of the methane seep was important and novel. In fact, when the Okeanos science team wanted to archive their sonar recordings with NOAA’s National Center for Environmental Information, officials said they didn’t have the capacity to store it. But a few years later, after the Deepwater Horizon disaster, there was a new appreciation for the value of using sidescan sonar data to detect natural seeps of methane, something important for understanding the global carbon budget and how hydrocarbons move from the Earth’s crust to the ocean and atmosphere, as well as petroleum leaks from commercial drilling operations.

Data from the multibeam sonar on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer provided a 3D image of an underwater gas plume rising 1,400 meters (4,590 feet) from the seafloor off the California Coast in 2009. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research.

“After Deepwater Horizon happened, then water column data was all the rage,” Malik said. “There was a national priority. Now we have a centralized place to archive all the water column data.”

Since then, multibeam sonar devices have been deployed to discover unusual gas seeps in the Gulf of Mexico and along the Atlantic Seaboard. Researchers aboard the Okeanos Explorer have pushed the boundaries of the science and technology that led to these discoveries.