Roy Cullimore: Video Transcript

Hear Roy Cullimore talk about his job. Download (mp4, 272 MB).

Introduction

My name is Roy Cullimore and I work at Droycon Bioconcepts Incorporated, in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. I am the President and general partner and research director of the company. Most of the time we work on Biological Activity Reaction Test kits that we manufacture here and send out for distribution around the world. My job is the love of my life, which is doing research and developing things for people who can actually use them.

"For the 2004 Titanic Expedition I had the privilege of having dove to the ship three times in the submarine in 1996, 1998, and 2003."

The 2004 Titanic Expedition

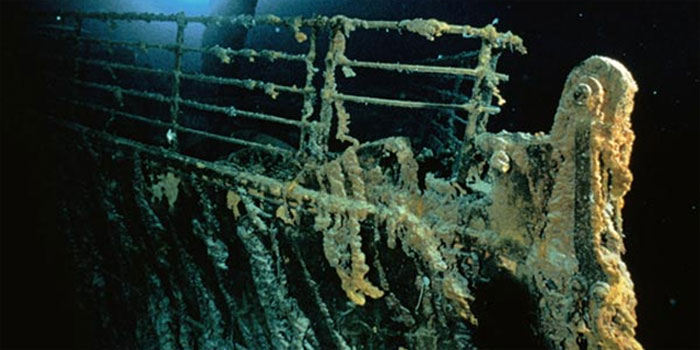

My responsibility when I got out to sea was to look at the way these steel ships are gradually falling apart, breaking apart and rusting. Rusting is the key word because I am not looking at rust as a chemical thing but as a microbial thing. Microorganisms are in there that are taking the iron out of the steel to build their community and homes, a place where they will live.

The biggest challenge at sea is that we are dealing with way down there in the deep ocean where the temperature is almost freezing, the salt concentration is saturated and if I were out there I wouldn’t survive a second. But the microbes and the fish and the crabs are all living in this environment and I’m fascinated by the fact that this is an extreme place to be living but they are all living there. I’m fascinated by the amount of variation of life that can occur.

For the 2004 Titanic Expedition I had the privilege of having dove to the ship three times in the submarine in 1996, 1998, and 2003. So I’ve seen the ship. It grabs you emotionally. It stimulates your curiosity and gets the science going to the point that I’ve put experiments down on the ship in 1996 and I’ve had experiments on the ship in 1998 that were still there in 2004 that we got to bring back. So we are developing real science. Science doesn’t happen in a shoebox. It doesn’t happen in a laboratory. It doesn’t happen over night. Real science is a scientific development. When I’m working with Titanic it is a beautiful challenge because the science there will go on for one hundred or two hundred years. I’m excited to be a part of that and a part of history. This expedition was a particular challenge because first of all the Titanic had gone through a growth of rusticles. These are the rusticles growing outside of the ship. Even more inside the ship we can only just see that they were growing much more rapidly between 1996 and 1998. Then in 2003 they were starting to drop away, and they are still dropping away. We have a life cycle and what we’re seeing is that the rusticles are going to come back again. So what is making them come back? This is opening up new horizons and new challenges and I’m hoping that we will be able to find value in the work that we are doing with these rusticles. We are from nature’s point of view recycling the iron. After all, we stole he iron from nature and we made the steel. We made a beautiful ship that tragically sank on its maiden voyage and now nature is slowly taking it back.

"What we did was recover two steel test platforms from the Titanic."

Rusticles

What we did was recover two steel test platforms from the Titanic. The first one was from the stern section just below the main engines. The second one was from the port side. In each case what happened was that we would go down to the site and the robot arm would come out, grab the platform, bring it up and then put it into a biological box which was on the side of the ROV. Then the rig was closed down and the box went back into Hercules. Then Hercules was brought back up onto the deck and then I go out and the biological box is opened. When we opened the box it was quite weathered from the ocean and very salty water. So we had to remove this very salty water out of the box and then the platform could be lifted up. When we were at the 2004 Titanic we brought back two of the test platforms, one from the stern of the ship and one from the port side. What we’ve done here is just project it with a plastic bag, which I have to cut open. We’ve used lots of duct tape to protect the platform itself. Once we’ve broken this open we can begin our work on the platform. This is the float that enabled the Hercules ROV arm to grab the platform and lift it into the biological box. Here is the information about the platform. This was the one that was on the stern of the ship. These are twisted, tempered, and hammered.

The top one here is a twisted… tempered… the next one is hammered… the next one is twisted and tempered… twisted. So the difference in these two is that this one was heat-treated and if you look at the rusticle growth between these two there is very little difference. The rusticles grew as happily on this one as they did on this one. And then we come down to the next set of steels and we again see that we get the most growth on the twisted set of steels although it was tempered a lot. So that means that on the Titanic, where the steel has been twisted, you can expect to see more rusticle growth. And it is interesting that on the stern section of the ship, she came down much harder and she smacked into the ocean floor somewhere around fifty miles per hour and there was a lot of twisting of steel and they suspect that the rusticles began to grow. It is also because this is where the refrigeration was which had the food. We did some calculation in 1998 and it looks like about fifteen tons of carbohydrates, five tons of protein, and about four and a half tons of fat was there and available for the microbes as soon as the ship was on the floor. So the first growth, not necessarily rusticles, but the first growth of microbes began there. What is also fascinating is that last year in 2003, this rusticles did not exist. This rusticle, which is about four inches long, grew between 2003 and 2004. That’s at least a quarter of an inch a month. The microorganisms or rusticles are able to capitalize on any electrical changes that occur between these individual steel coupons and this is an area of science, which is very new and very exciting and will keep us exploring. At the Titanic site today we still have two of these platforms. One of them is sitting right by the stern at the front of the ship and the other one is by the bow of the deck. Those are still there for us to bring back.

"We can now much better project the rate of which the Titanic is going to degrade."

Closing Comments

And we can now much better project the rate of which the Titanic is going to degrade. It is always a surprise to me that as a retired career professor, and no longer associated with the university and my career become my dreams. I don’t have to think I need to be validated because someone says this is good. If I want to do it. I’ll do it. In that respect the work on the Titanic that I have been doing over the last forty years validates that. I have been called the slime scientist, which I call an honor because slimes are such yucky things and would there ever any science in there? Science is in serious trouble. We've become so linear and we never look to the left or look to the right and we never understand quite enough the other sciences. My degrees are in agriculture where you have to understand all aspects of various sciences in order to operate in agriculture. It’s a fortuitous advantage and I think we are going to have to go back to that. We are going to have to stop dreaming of going back to the DNA stars and coming down to reality. We live here and we don’t want to become extinct. What are we as a species going to collectively do to make us feel comfortable about what we are doing and how it can be good for the planet.

For students following a career it science, first of all science is not hard and narrow. If you want to have a real impact in science, don’t forget to breathe and create and above all else innovate.

Return to profile