Dr. Peter Etnoyer: Video Transcript

Hear Peter talk about his job and what it's like to conduct science while at sea. Download (mp4, 80 MB).

How do we preserve deep sea coral?

There are over 100 species of deep-sea coral, so we must first confirm the identity of the sample. To do this, we remove the branch from its preservative, place some tissue on a slide, and put the slide under a microscope to reveal the sclerites. Sclerites are microscopic bones floating freely in the tissue. Every species has a unique set of sclerites with different shapes. Some have cool names like “Thornstar,” “Warty Club,” and "Caterpillar." (Note: the images in video are not sclerites, they are corals.)

We use these sclerites to confirm the identity of a deep-sea coral. Once we know the species name, we place the specimen in long-term storage for future research applications. We might wish to examine a coral’s DNA through molecular analysis or examine its chemical structure for biomaterials applications. This kind of research requires a strong background in chemistry and biology.

I hope these videos have been useful, and I hope that one day some of you will join us in the halls of science.

Finding deep sea coral: scientists like Dr. Etnoyer use a multibeam echo sounder to scan the ocean floor for deep sea coral.

How do we find deep sea coral?

We do this by using a multibeam echo sounder to scan the seafloor, the same way an orbital satellite scans a planet. The process requires a working knowledge of electronics, computers, and field survey techniques.

To learn more, I want you to go to a Web page called “Measuring Mountains in the Sea,” and watch some fly-through movies of seamounts in the Gulf of Alaska and submerged banks in the Gulf of Mexico. All these are perfect candidates for deep-sea coral habitat.

Collecting deep sea coral: this is accomplished using manned submersibles and ROVs.

How do we collect deep sea coral?

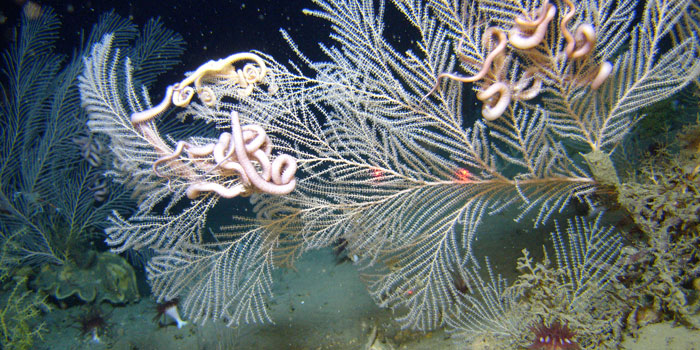

After we scan the seafloor and identify our targets, we give the coordinates to the dive teams, and ready our vessel for a journey to the deep. We might use either a manned submersible, or a remotely operated vehicle.

Each type of vessel has different advantages. ROV’s can stay down for long periods of time but they are tethered to the surface ship. Manned submersibles are untethered, move freely, and provide a rare human perspective. Regardless of the platform we use, at some point we must engage a manipulator arm to pluck a deep-sea coral colony and bring it to the surface.

This summer I went collecting with a giant robot in 1,500 feet of water in the Gulf of Mexico. The most important skills I needed were patience, experience, and familiarity with invertebrate zoology and taxonomy. If you are interested in more information about this, go to the Web page called, “The Life Cycle of a Specimen” and you will discover what we do with a coral once we bring it to the surface.

Back at the museum: Dr. Etnoyer identifies deep sea coral by examining preserved coral slices with a microscope for comparison of the coral's sclerites which are different for each species.

How do we preserve deep sea coral?

There are over 100 species of deep-sea coral, so we must first confirm the identity of the sample. To do this, we remove the branch from its preservative, place some tissue on a slide, and put the slide under a microscope to reveal the sclerites. Sclerites are microscopic bones floating freely in the tissue. Every species has a unique set of sclerites with different shapes. Some have cool names like “Thornstar,” “Warty Club,” and "Caterpillar." (Note: the images in video are not sclerites, they are corals.)

We use these sclerites to confirm the identity of a deep-sea coral. Once we know the species name, we place the specimen in long-term storage for future research applications. We might wish to examine a coral’s DNA through molecular analysis or examine its chemical structure for biomaterials applications. This kind of research requires a strong background in chemistry and biology.

I hope these videos have been useful, and I hope that one day some of you will join us in the halls of science.

Published September 3, 2018

Return to profile